Lightening

Sources: Wildfire Assessament System and ThoughtCo and Treehugger

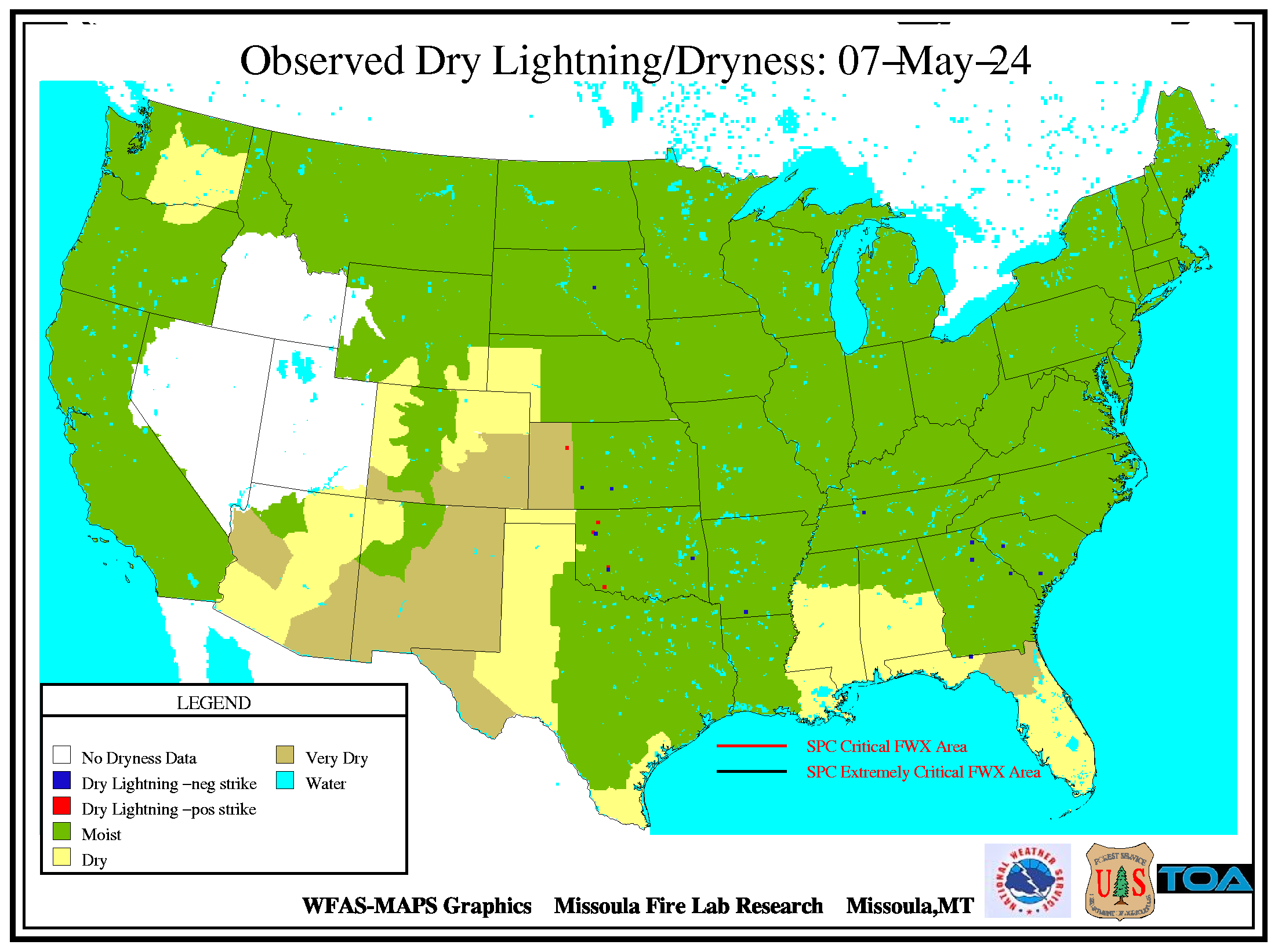

Dry Lightening

Heat lightning, sometimes called "dry lightening" is the nickname given to the silent lightning strikes and faint flashes of light that are visible on the distant horizon on some warm, humid summer nights. To the naked eye, these flashes appear to occur without a nearby thunderstorm or rainstorm. Such dry thunderstorms are often the culprits behind massive wildfires when lightning ignites a dry fuel source on the ground during fire weather season, which is the hot summer months. Although there's no rain, at least at ground level, these storms still pack plenty of lightning. When lightning strikes in these arid conditions, it's called dry lightning and wildfires can easily erupt. Vegetation and flora are often parched and readily ignitable.

Dry lightning shouldn't be confused with dry thunderstorms, as these two are different phenomena. Dry lightning is called "dry" because it appears to occur sans thunderstorm or rainstorm; but in reality, dry lightning is associated with a rainstorm, the rain is just too distant to be visible. Dry thunderstorms produce thunder, lightning, and precipitation, but are called "dry" because their rainfall evaporates before reaching the ground. In meteorology, this event is called virga.

Strong winds often develop around dry thunderstorms as the evaporating precipitation causes excessive cooling of the air beneath the storm, which increases its density and thereby its weight relative to the surrounding air. This cool air then descends rapidly and fans out upon impacting the ground, an event often described as a dry microburst. As the gusty winds expand outward from the storm, dry soil and sand are often picked up by the strong winds, creating dust and sand storms known as haboobs.

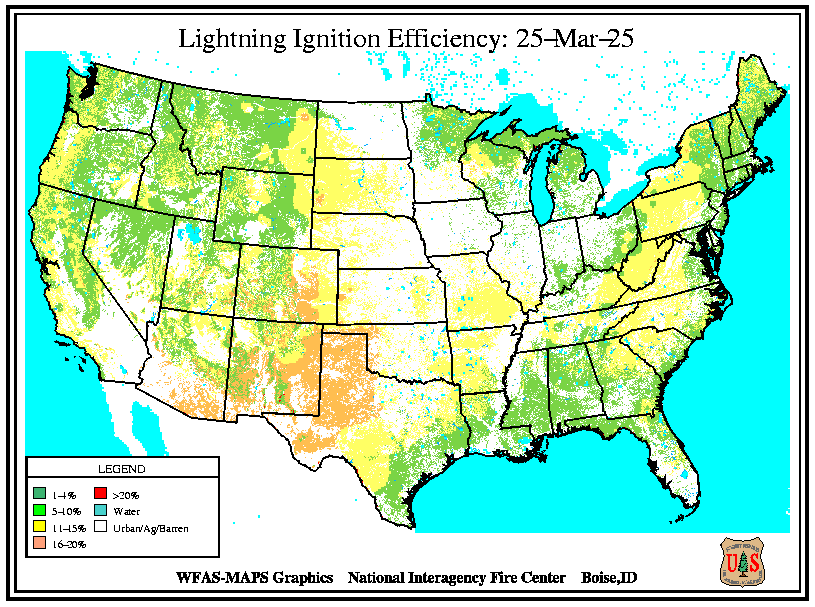

Lightening Efficiency Ignition

Lightning fires are started by strikes to ground that have a component called a continuing current. All positive discharges have a continuing current, and about 20% of negative discharges have one. Ignition depends on the duration of the current and the kind of fuel the lightning hits. Ignition in fuels with long and medium length needle cast, such as Ponderosa pine and Lodgepole pine, depend on the fuel moisture. Ignitions in short needled species, such as Douglas fir depend far more on the depth of the duff layer than on the moisture. Spread of the fire after ignition usually depends on fuel moisture in all cases.

If the efficiency is high, then about 9 discharges will result in one ignition; if the efficiency is extreme, about 5 or fewer discharges will result in an ignition.